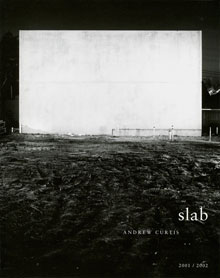

Slab

‘GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE’, essay for Slab, an exhibition by Andrew Curtis, Christine Abrahams Gallery 2003

Andrew Curtis has photographed the concrete slabs of industrial pre-fab architecture. Seen at Christine Abrahams Gallery in July his exhibition Slab showed the banal concrete walls and steel struts transformed into sites of magic, danger and struggle. Photographing at night using a dramatic lighting technique, Curtis has created a series of hallucinations of looming monoliths, criss-crossing shadows and pulsing, glowing forms.

For his previous exhibition Volt, Curtis photographed another unlikely subject from the built environment, electricity substations. These were depicted as pop-cultural contraptions, like the robots in 1950s sci-fi movies. But Slab is dark. The large black and white prints are strange and the secret places in them mysterious, evoking an atmosphere the Surrealists liked to call “the uncanny.” The title Slab has a neat brevity, and of course recalls the name of the morgue table, a funereal connotation backed up in the pictures.

In a series of images blandly titled Toorak Rd (as though inviting the viewer to see for themself) monoliths rise up, shrouded in shadow but giving off an unnatural light of their own. Beams hold back huge threatening blocks, resisting unknown forces. In images shot in other locations, slabs lie on the ground like coffins, glowing with an eerie inner light. The work is primal, recalling the monumental structures of sculptor Richard Serra: the allure of brutal materials and massive scale, but seen in a nightmare.

This gothic vision is at odds with much photography of buildings in this country which tends to draw out the historical memory of place, or else engage in a deadpan presentation of what Robin Boyd called The Australian Ugliness. The threatening shadows of Slab seem European by contrast and recall the paranoid fantasies of German Expressionist Cinema, Dr Caligari and Nosferatu and the like.

Film refernces abound in Curtis’ work and should be seen as a dialogue with other (film) artists. His abiding admiration for the cinema of David Lynch, especially of Eraserhead with its ruined industrial landscape, has given him a kind of compass-bearing in several projects. This is not a case of copying old masters, but a distant collaboration on a series of artististic problems: the primacy of dream-life and the imagination, the unreliability of appearances, the mystery hidden in ordinary things.

Transforming ordinary things is the natural domain of photography and the photographic-ness of Slab is one of its pleasures. Shot with a large format camera and printed with traditional darkroom, not digital, techniques, the aesthetic is one of classic black and white photography. Tungsten lighting is used in a way that is reminiscent of the great Wolfgang Sievers’ industrial photographs, although brought to a higher pitch of intensity.

Slab is not about slab architecture. We are not seeing an efficient engineering process putting up shiny new apartment buildings. It is really the opposite. What Curtis shows is not a beginning but an end. The primary materials of concrete, steel and rock, the beams, panels and excavations are depicted archaeologically, as though we are coming across their ruins in some distant future. Rather than seeing images of a rational technology we have glimpses of something barbarous and pagan. And, as in all Curtis’ work, an apparition of the ghost in the machine.